-

Tuesdays 10 o’clock at the CERN library

Tuesdays 10 o’clock was an important time for physicists working at CERN. Every week at that time, starting in the early 1960s, a ritual would play out that also structured much of the local research community’s habits of acquiring new information of what was happening in high-energy physics and related fields. As one informant who used to work for the Scientific Information Service at CERN described to me:

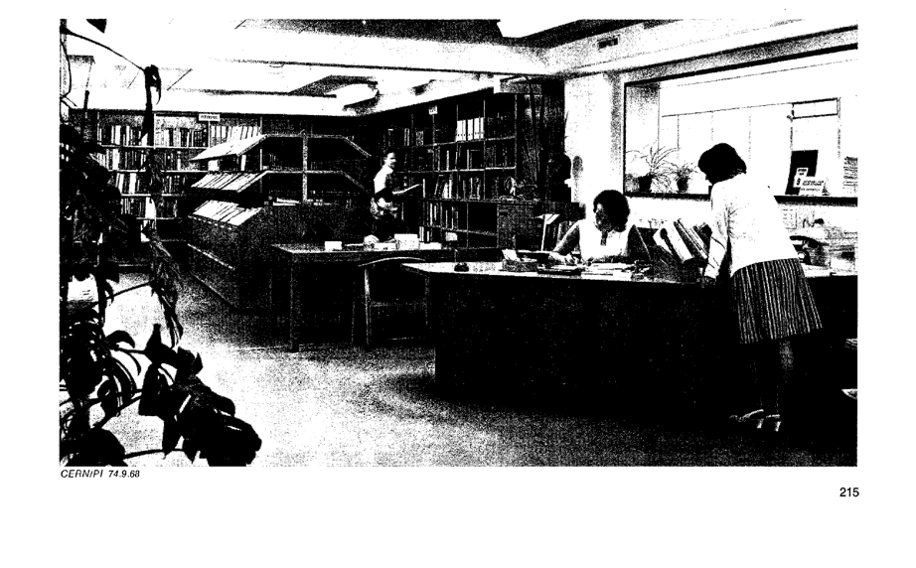

“A librarian would appear carrying a large pile of newly-received preprints, each one marked with its report number for subsequent filing. She would lay out the preprint one-by-one on the display on top of the wooden drawers where the back collection was stored, the preceding ones were taken away for copying in response to requests and later in the day filed. Each preprint had a small slip attached by a paper clip to the first page, on which one could give one’s name if one wanted to be sent a copy in the internal mail.”

Image from September 1968 CERN Courier (No. 9 Vol. 8) showing the preprint displays at the library in the back. “Preprints” have served as an important means to rapidly inform members of the global physics community about the newest developments and findings in the field. While personal contact was essential to keep afloat of rapid developments until the 1940s, the sharing of lecture notes, unpublished reports, or copies of manuscripts through the mail or at gatherings had later gained considerable importance to compensate for the dispersion of the community. However, as historian David Kaiser notes: “No one could afford to rely on published sources alone.”1 High-energy physicists are known as a lot that thrives on oral communication and personal networks. The infamous discussions in front of blackboards have been a staple of the popular culture of physics across the 20th century.

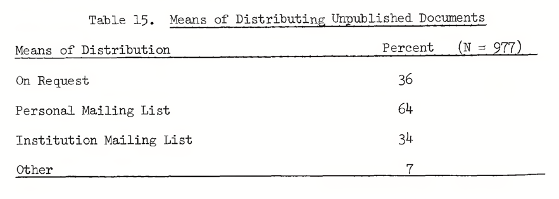

Thus, the practice of sharing one’s notes or manuscripts was based on personal contacts. Authors would keep track of those researchers, who were active in the same research are or who could otherwise be interested in ones work. So, asking them to send their papers and notes to an institution was a breach in a system based on a convention of “private communication”. In a study of communication behaviours among high-energy theoretical physicists conducted for the American Institute of Physics and published in 1967, the authors reveal that the majority of scientists rely on “personal mailing lists” to keep up with the newest developments in the field.2

The library at CERN played a major role in the early developments of a preprint culture in physics. In the late 1950s, the librarian Luisella Goldschmidt-Clermont ventured on a daring mission: She began soliciting preprints from physicists to collect and display at the library. When Mrs. Goldschmidt-Clermont started asking physicists to not only send their unpublished papers to the CERN library to put on display for the local research community, but also asked to share their personal contacts with the institution, she was introducing radical changes into the communication behaviors of high-energy physicists. However, while it was unconventional to request that physicists send their preprint papers to the library instead of directly to their network of colleagues, the local physicists, with whom she spoke, showed support for her project; while the higher echelons at the CERN library voiced concern that her preprint system might distort the mechanisms for making claims to priority in science, which is usually registered through formal publication. So, Goldschmidt-Clermont took recourse to the one argument that couldn’t be denied: the mandate of CERN. In a proposal to the directorate in 1961 to set up the preprint collection and distribution system, she therefore emphasized the “openness” policies that were enshrined into the founding of CERN:

“… CERN’s contribution to this [preprint system] is intended mostly as a ‘conversion’ of its present efforts in the field of preprints towards this project. CERN would benefit directly form this conversion as more material would become available to its scientists. CERN would also benefit indirectly from this conversion; by an inexpensive gesture of good will, it would share with the Member States laboratories a privilege (the preprint service) which CERN is almost alone to enjoy at present in Europe; by its Convention, CERN is bound to contribute to ‘international cooperation in nuclear research, … This cooperation may include … the promotion of contacts between … scientists, the dissemination of information, …’ (CERN Convention, Article II, para 3 c)”

Thus, it could be argued that the CERN library is were important groundwork for the current culture of “open science” were laid in the 1960s.

- David Kaiser (2005). Drawing Theories Apart. The Dispersion of Feynman Diagrams in Postwar Physics. Chicago/London: University of Chicago Press. ↩︎

- Miles A. Libbey, Gerald Altman (1967). The Role and Distribution of Written Informal Communication in Theoretical High Energy Physics. New York: American Institute of Physics. ↩︎

-

DESY and the High-Energy Physics Index

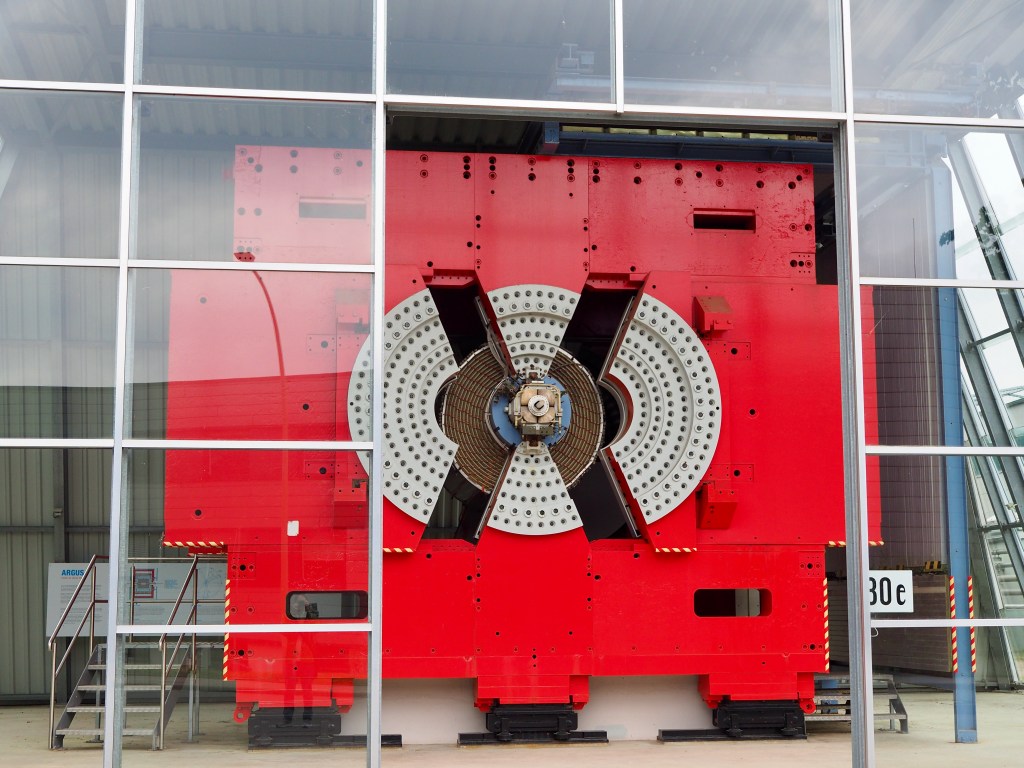

From May 21 to 23, 2024, I was a guest at the “Deutsches Elektron-Synchronton” (DESY), Germany’s national accelerator center located in the North-East of Hamburg. It was established in 1959 and has contributed substantially to particle physics research over the decades. What is less known is that the library at DESY began publishing a bi-weekly “High-Energy Physics Index” (HEP Index) in 1963, the print-out of a computer database of physics literature, which included a list of recent preprints, where all the bibliographical information was sorted by author, subject, and report number indexes. As an international publication, the HEP Index has contributed significantly to the normalization and formalization of preprints in the field, and therefore constitutes a crucial bibliographic instrument in the history of preprints.

The decommissioned ARGUS detector visitors see as they enter the DESY site. Photo (c) the author. During my visit, I was a guest of DESY’s library, located in one of the central administrative buildings on campus. I had the pleasure to learn much about the early work at the library from Dietmar Schmidt, who began working at the library in 1973, became the head in 1982, and retired in 2007, as well as from Antje Daum, who has been a librarian at DESY since the 1980s. Both were very kind in showing me around the site and displayed a sincere interest in my project.

A printed issue of the HEP Index, first published in 1963 by DESY. Photo (c) the author, courtesy of the DESY library. Schmidt told me that what distinguished the efforts at DESY from existing ones to catalog the physics literature at SLAC or CERN at the time was, first of all, that the literature documentation was not restricted to preprints and reports, but covered “conventional” physics literature as well, i.e., journal papers, conference proceedings, and (text) books. Second of all, literature documentation at the DESY library was computerized from the very beginning. Schmidt, who studied physics at the University of Hamburg, was employed in part because he possessed expertise in computer programming. When he joined DESY in 1973, he said that the first task Kurt Mellentin, then director of the library and documentation service, gave him was to “rewrite the existing programs for literature documentation – correction programs, print programs for the HEP Index – which were all coded in IBM Assembler, into PL/I,” which took him one and a half years. Schmidt told me that PL/I was introduced, “because it enabled fine word processing [schöne Textverarbeitung]” and that it was in use until the mid-1990s, when Unix systems took over.

Magnetic tapes containing the cumulative database of the HEP Index. Photo (c) the author, courtesy of DESY. Compiling the HEP Index required not only bibliographic skills, but also a considerable expertise in high-energy physics. For this reason, many who worked on making the Index were (former) physicists now working in the library and documentation service. Physicists, active in one of the many of DESY’s research groups, were also regularly consulted for their understanding of the field. Compiling the Index for the bi-weekly publication was rather unconventional: the newest library acquisitions – journal issues and conference proceedings – were scanned “manually” for relevant titles to include in the index. Additionally, a system had established, similar to CERN and SLAC, in which authors would send their unpublished or submitted preprints to the DESY library. These too were reviewed for inclusion in the HEP Index.

The HEP Index had a further significance, not just as a bibliography of high-energy physics literature; it also contributed to the preprints and reports database at SLAC in California. beginning in the early 1960s, the DESY library shared its cumulative database with the SLAC library, particularly for its lists of “conventional” publications. The magnetic tapes containing the bibliographic information were shipped across the Atlantic in exchange for tapes containing the preprints acquired at SLAC. This transatlantic connection eventually fed into the establishment of the global high-energy physics literature online database SPIRES at Stanford, which today is the INSPIRE website containing all the bibliographical information in the field.

-

What is Preprint Culture?

Preprint Culture is a book project that employs media studies and book history to examine how science came to speak and traffic in preprints. The goal is to deliver a compelling media history that can help make sense of the current status of preprints in science as well as shed light on how processes of digitization have impacted scientific communication, both culturally and socially. Preprints are scientific texts, often intended for formal publication in a peer-reviewed journal, which are circulated to colleagues beforehand as preliminary versions. While preprints originated in physics after World War II, with the informal practice of privately forwarding paper drafts to other researchers via mail, distribution of preprints has become very much formalized today through the cataloging of preprints in large online databases and the use of public servers like arXiv.org. During the recent Covid crisis, preprints gained widespread publicity when scientists and physicians rapidly disseminated research results worldwide, even before peer-review, to help orient clinical action as well as public health decisions.

Screenshot of the arXiv.org preprint website (taken on 28. July 2023). The basic idea of Preprint Culture is to understand preprints as media technologies, whose recording, storing, and transmitting capabilities have immense cultural significance. Just in the way files have been studied as media technologies, for instance, I want to understand preprints as acting like (imperfect) “recording devices”, which register things that happen in research “in the medium of writing”.1 Since a defining feature of preprints is their rapid circulation to a discrete community or research culture, however, rather than dissemination to the general academic public, the project views preprints in analogy to “information genres”.2 This means bringing them into proximity of the wide range of documents, such as memos, reports, letters, or forms, that exist to relay information through the organizational structures of modern work environments.3 My thesis is that preprints reveal a complex relationship of genre and format in scholarly texts that helps elucidate their uncertainty as either prepublication drafts and manuscripts on the one hand or formal publications on the other.

Preprint Culture then traces the history of preprints from the postwar era to the present as an exercise in what in media studies is called “format theory”.4 This implies studying the development of different regimes responsible for handling and circulating preprints in various formats – from typescripts and photocopies sent by mail through TeX and PostScript files distributed via email to PDFs stored on online repositories – and asking what they reveal about the complex material conditions that enabled managing and processing information in late-modern science. Preprint Culture sets out to tell the history of preprints as an investigation of the technologies, concepts, protocols, and underlying infrastructures that enabled the material encoding of data for the purpose of rapid transmission and for storing scientific information. One aim of the project is to reveal how seemingly mundane practices like typing, photocopying, mailing, filing, and cataloging – and the people behind them – evolved into becoming the infrastructures and technologies used for handling preprints. Form this perspective, librarians – and often women – have contributed significantly to the formation of science’s preprint culture.5

Analytically, Preprint Culture looks for what can be called “bibliographic imaginaries”.6 By these I want to understand the ideas about how preprints belong into the bibliographic universe of scientific information and the perceptions of how they related to other forms and genres of communication. Imaginaries of information management and of scholarly media, such as the scientific journal, the encyclopedia, or the database, have been driven by themes such as “information overload”, “techno-utopianisms” for handling scholarly information, or “access fantasies” to the body of scientific literature.7 Preprint imaginaries thus offer important insights into how actors and institutions imagined their use or function as a medium, how they could support (or harm) science, and which technologies and practices could help establish and control such a system of scientific communication.

The physical preprints newsletter distributed by the SLAC library was discontinued in 1993. Historically, Preprint Culture focuses on two important centers for research in high-energy physics – the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN) in Geneva, Switzerland, and the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center (SLAC) in California, which contributed greatly to turning circulating paper drafts into serious bibliographic formats. The aim is to highlight their libraries as places that developed various regimes for recording, ordering, and sharing preprints and also pioneered the digitization of the preprint system. CERN was the institution to first subject the initially informal means of scientific communication via preprints to a bibliographic regime in the late 1950s. Later, moreover, the center was also the institution at which, in 1989, the World Wide Web was invented and released to the world, making possible today’s preprint websites. SLAC, in turn, made informing the physics community about preprints a regular event after its founding in 1962. The center’s library collected and cataloged new high-energy physics preprints and published the listings via their newsletter “Preprints in Particles and Fields” to participating physics research institutes around the globe. It was also here that huge strides were made toward digitizing the preprint catalog with the introduction of the Stanford Physics Information Retrieval System (SPIRES-HEP) in 1974.

- Cf. Cornelia Vismann (2008). Files. Law and Media Technology. Trans. Geoffrey Winthrop-Young. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ↩︎

- Cf. Lisa Gitelman (2014). Paper Knowledge. Toward a Media History of Documents. Durham/London: Duke University Press; John Guillory (2004). The Memo and Modernity. Critical Inquiry 31(1). 108–132. ↩︎

- JoAnn Yates (1989). Control Through Communication. The Rise of System in American Management. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ↩︎

- Jonathan Sterne (2012). MP3. The Meaning of a Format. Durham/London: Duke University Press. Cf. Dennis Tenen (2017). Plain Text. The Poetics of Computation. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Formats define the operational rules for technology to process data, determine the affordances of a medium, and control and delimit access to “content”. Formats depend on a range of factors, such as media, infrastructures, protocols, codes, standards, and software. The same text not only depends on different technical and social conditions of reception with change of format; it is thereby also afforded different functions and meanings within different cultural settings. ↩︎ - Two pivotal librarians in this context were Luisella Goldschmidt-Clermont at CERN and Louise Addis at SLAC. ↩︎

- Cf. Andrew Piper (2009). Dreaming in Books. The Making of Bibliographic Imagination in the Romantic Age. Chicago/London: University of Chicago Press. ↩︎

- Cf. Ann M. Blair (2010). Too Much to Know. Managing Scholarly Information before the Modern Age. New Haven/London: Yale University Press; Geoffrey C. Bowker (2005). Memory Practices in the Sciences. Cambridge, MA/London: MIT Press; Alex Csiszar (2018). The Scientific Journal. Authorship and the Politics of Knowledge in the Nineteenth Century. Chicago/London: University of Chicago Press; Chad Wellmon (2015). Organizing Enlightenment. Information Overload and the Invention of the Modern Research University. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ↩︎

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.